If you know me, then you’ll know that “Guilty Robots, Happy Dogs” pretty much had me at the title.

It’s obviously very relevant to our interests at BERG, and I’ve been trying to read up around the area of AI, robotics and companions species for a while.

Struggled to get thought it to be honest – I find philosophy a grind to read. My eyes slip off the words and I have to read everything twice to understand it.

But, it was worth it.

My highlights from Kindle below, and my emboldening on bits that really struck home for me. Here’s a review by Daniel Dennett for luck.

“Real aliens have always been with us. They were here before us, and have been here ever since. We call these aliens animals.”

“They will carry out tasks, such as underwater survey, that are dangerous for people, and they will do so in a competent, efficient, and reassuring manner. To some extent, some such tasks have traditionally been performed by animals. We place our trust in horses, dogs, cats, and homing pigeons to perform tasks that would be difficult for us to perform as well if at all.”

“Autonomy implies freedom from outside control. There are three main types of freedom relevant to robots. One is freedom from outside control of energy supply. Most current robots run on batteries that must be replaced or recharged by people. Self-refuelling robots would have energy autonomy. Another is freedom of choice of activity. An automaton lacks such freedom, because either it follows a strict routine or it is entirely reactive. A robot that has alternative possible activities, and the freedom to decide which to do, has motivational autonomy. Thirdly, there is freedom of ‘thought’. A robot that has the freedom to think up better ways of doing things may be said to have mental autonomy.”

“One could envisage a system incorporating the elements of a mobile robot and an energy conversion unit. They could be combined in a single robot or kept separate so that the robot brings its food back to the ‘digester’. Such a robot would exhibit central place foraging.”

“turkeys and aphids have increased their fitness by genetically adapting to the symbiotic pressures of another species.”

“In reality, I know nothing (for sure) about the dog’s inner workings, but I am, nevertheless, interpreting the dog’s behaviour.”

“A thermostat … is one of the simplest, most rudimentary, least interesting systems that should be included in the class of believers—the class of intentional systems, to use my term. Why? Because it has a rudimentary goal or desire (which is set, dictatorially, by the thermostat’s owner, of course), which it acts on appropriately whenever it believes (thanks to a sensor of one sort or another) that its desires are unfulfilled. Of course, you don’t have to describe a thermostat in these terms. You can describe it in mechanical terms, or even molecular terms. But what is theoretically interesting is that if you want to describe the set of all thermostats (cf. the set of all purchasers) you have to rise to this intentional level.”

“So, as a rule of thumb, for an animal or robot to have a mind it must have intentionality (including rationality) and subjectivity. Not all philosophers will agree with this rule of thumb, but we must start somewhere.”

We want to know about robot minds, because robots are becoming increasingly important in our lives, and we want to know how to manage them. As robots become more sophisticated, should we aim to control them or trust them? Should we regard them as extensions of our own bodies, extending our control over the environment, or as responsible beings in their own right? Our future policies towards robots and animals will depend largely upon our attitude towards their mentality.”

“In another study, juvenile crows were raised in captivity, and never allowed to observe an adult crow. Two of them, a male and a female, were housed together and were given regular demonstrations by their human foster parents of how to use twig tools to obtain food. Another two were housed individually, and never witnessed tool use. All four crows developed the ability to use twig tools. One crow, called Betty, was of special interest.”

“What we saw in this case that was the really surprising stuff, was an animal facing a new task and new material and concocting a new tool that was appropriate in a process that could not have been imitated immediately from someone else.”

“A video clip of Betty making a hook can be seen on the Internet.”

“We are looking for a reason to suppose that there is something that it is like to be that animal. This does not mean something that it is like to us. It does not make sense to ask what it would be like (to a human) to be a bat, because a human has a human brain. No film-maker, or virtual reality expert, could convey to us what it is like to be a bat, no matter how much they knew about bats.”

“We have seen that animals and robots can, on occasion, produce behaviour that makes us sit up and wonder whether these aliens really do have minds, maybe like ours, maybe different from ours. These phenomena, especially those involving apparent intentionality and subjectivity, require explanation at a scientific level, and at a philosophical level. The question is, what kind of explanation are we looking for? At this point, you (the reader) need to decide where you stand on certain issues”

“The successful real (as opposed to simulated) robots have been reactive and situated (see Chapter 1) while their predecessors were ‘all thought and no action’. In the words of philosopher Andy Clark”

“Innovation is desirable but should be undertaken with care. The extra research and development required could endanger the long-term success of the robot (see also Chapters 1 and 2). So in considering the life-history strategy of a robot it is important to consider the type of market that it is aimed at, and where it is to be placed in the spectrum. If the robot is to compete with other toys, it needs to be cheap and cheerful. If it is to compete with humans for certain types of work, it needs to be robust and competent.”

“connectionist networks are better suited to dealing with knowledge how, rather than knowledge that”

“The chickens have the same colour illusion as we do.”

For robots, it is different. Their mode of development and reproduction is different from that of most animals. Robots have a symbiotic relationship with people, analogous to the relationship between aphids and ants, or domestic animals and people. Robots depend on humans for their reproductive success. The designer of a robot will flourish if the robot is successful in the marketplace. The employer of a robot will flourish if the robot does the job better than the available alternatives. Therefore, if a robot is to have a mind, it must be one that is suited to the robot’s environment and way of life, its ecological niche.”

“there is an element of chauvinism in the evolutionary continuity approach. Too much attention is paid to the similarities between certain animals and humans, and not enough to the fit between the animal and its ecological niche. If an animal has a mind, it has evolved to do a job that is different from the job that it does in humans.”

“When I first became interested in robotics I visited, and worked in, various laboratories around the world. I was extremely impressed with the technical expertise, but not with the philosophy. They could make robots all right, but they did not seem to know what they wanted their robots to do. The main aim seemed to be to produce a robot that was intelligent. But an intelligent agent must be intelligent about something. There is no such thing as a generalised animal, and there will be no such thing as a successful generalised robot.”

Although logically we cannot tell whether it can feel pain (etc.), any more than we can with other people, sociologically it is in our interest (i.e. a matter of social convention) for the robot to feel accountable, as well as to be accountable. That way we can think of it as one of us, and that also goes for the dog.”

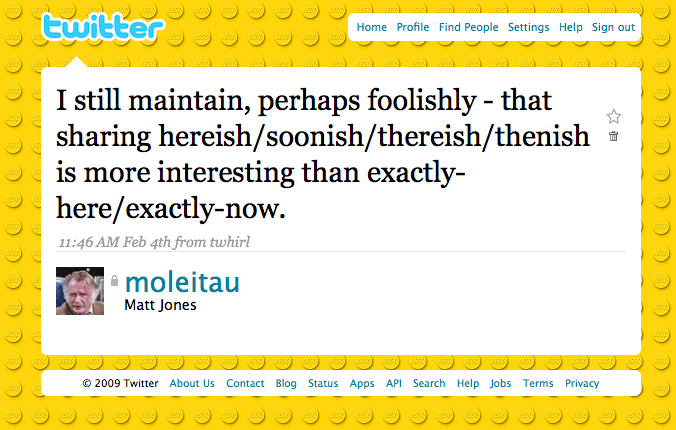

Often, he’s pointed out quite rightly, that location is a matter of routine. We’re in work, college, at home, at our corner shop, at our favourite pub. These patterns are worn into our personal maps of the city, and usually it’s the exceptions to it that we record, or share – a special excursion, or perhaps a unexpected diversion – pleasant or otherwise that we want to broadcast for companionship, or assistance.

Often, he’s pointed out quite rightly, that location is a matter of routine. We’re in work, college, at home, at our corner shop, at our favourite pub. These patterns are worn into our personal maps of the city, and usually it’s the exceptions to it that we record, or share – a special excursion, or perhaps a unexpected diversion – pleasant or otherwise that we want to broadcast for companionship, or assistance. This is a slide I’ve used a lot when giving presentations about Dopplr (for instance,

This is a slide I’ve used a lot when giving presentations about Dopplr (for instance,

In the Kiwifoo discussion, the group referenced the burgeoning ability of LBS systems to aggregating patterns of our movements.

In the Kiwifoo discussion, the group referenced the burgeoning ability of LBS systems to aggregating patterns of our movements.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)