“If something is ugly, say so. If it is tacky, inappropriate, out of proportion, unsustainable, morally degrading, ecologically impoverishing, or humanly demeaning, don’t let it pass. Don’t be stopped by the “if you can’t define it and measure it, I don’t have to pay attention to it” ploy. No one can precisely define or measure justice, democracy, security, freedom, truth, or love. No one can precisely define or measure any value. But if no one speaks up for them, if systems aren’t designed to produce them, if we don’t speak about them and point toward their presence or absence, they will cease to exist.”

Dancing with Systems, Donella Meadows

Category: Mind Gangsters

School days for grad shows

I had a wonderful experience last week of taking my ten year old daughter to the Goldsmiths BA Design show last week (thanks for the invite, Matt Ward!)

From the moment she walked through the door – her jaw dropped.

There was a delight and surprise that this might be something *they* could do one day.

That this might be what school turns into.

That the young people there who were only maybe a decade older could explore ideas, learn crafts old and new, make things, and ask questions with all that work.

And that they would be kind and clever and generous in answering her questions.

So – for sure, take your kids to the graduation shows, and design schools – maybe have a day where you invite local schools and get your students to explain their work to 10 year olds…?

p.s. Apologies to the students who’s work I have images of, but didn’t capture the author at the time of the show. I will try and get hold of a catalogue and rectify here ASAP!!!

“Smaller, cuter, weirder, fluttery”: Filtered for the #Breezepunk Future

I’m stealing Matt Webb’s “filtered for” format here – for a bunch of more or less loosely connected items that I want to post, associate and log as much for myself as to share.

And – I’ll admit – to remove the friction from posting something without having a strong thread or thesis to connect them.

I’ve pre-ordered “No miracles needed” by Mark Jacobson – which I’m looking forward to reading in February. Found out about it through this Guardian post a week or so ago.

The good news below from Simon Evans seems to support Prof Jacobson’s hypothesis…

Breezepunk has been knocking around in my head since Tobias mentioned it on this podcast…

Here’s the transcript of the video (transcribed by machine, of course) of Tobias describing the invention by scientists/engineers at Nanyang Polytechnic in Singapore – of a very small scale, low power way of harnessing wind energy:

“I found this sort of approach really interesting but mostly I like the small scale of it yes I like the fact that it’s you know it’s something that you could imagine just proliferating as a standard component that’s attached to sort of Street Furniture or things around the house or whatever it is you might put them on your windowsill because they’re quite small and they just generate like enough power to make a sensor work or a light or something and yeah it’s this this alternative future to the big powerful set piece green Energy Future that’s obviously being pushed and should continue to be pushed because that’s competing against the big Power and the fossil fuel future but I like this idea of like the smaller cuter weirder fluttery imagine it’s quite fluttery yeah so yeah so this is this is Breeze Punk everybody…”

I like the idea of it being a standard component – a lego. A breezeblock?

My sketching went from something initially much more like a bug hotel or one of those bricks that bees are meant to nest in, there’s something like a fractal Unite D’Habitation happening in the final sketch.

I also like #Breezepunk a lot – very Chobani Cinematic Universe.

I would like it to become… a thing. I suppose that’s why I’m writing this.

Used to be how you made things become things.

It’s probably not how you do it now, you need a much larger coordinated cultural footprint across various short-form streaming formats to make a dent in the embedding space of the LLMs.

Mind you, that’s not the same as making it ‘real’ or even ‘realish’ now is it.

A bit vogue-ish perhaps, to prove a point I asked ChatGPT what it knew about Breezepunk.

It took a while, but… it tried to turn into the altogether less satisfying “windpunk”…

I like making the cursor blink on ChatGPT.

The longer the better. I think it means you’re onto something.

Or maybe that’s just my Bartle-type showing again.

The production design of the recent adaptation of William Gibson’s The Peripheral seemed “fluttery” – particularly in it’s depiction of the post-jackpot London timeline.

Or perhaps the aesthetic is much more one of ‘filigree‘.

There’s heaviness and lightness being expressed as power by the various factions in their architecture, fashion, gadgets.

It’s an overt expression of that power being wielded via nanotechnology – assemblers, disassemblers constructing and deconstructing huge edifices at will.

Solid melting into air.

Into the breeze.

Punk.

Station Identification

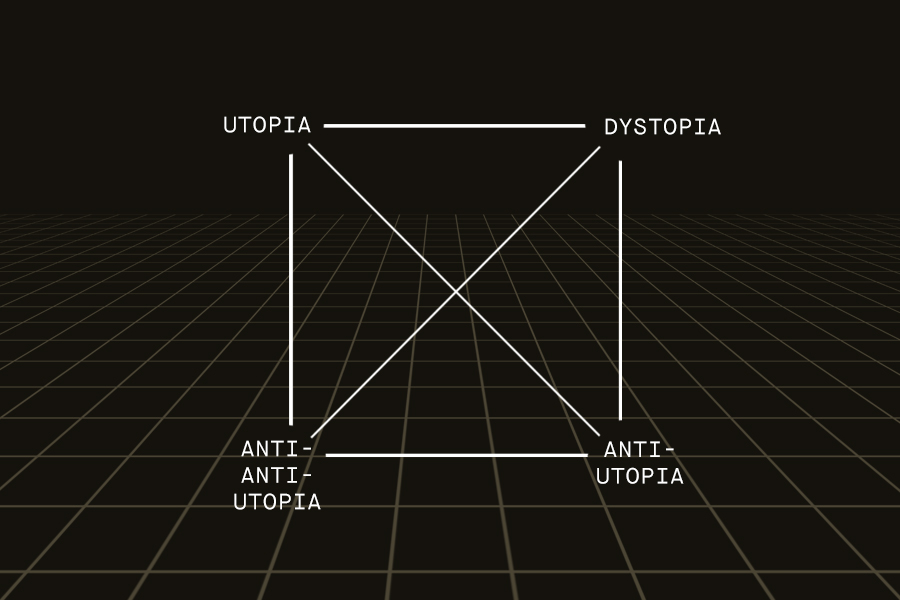

“It’s important to remember that utopia and dystopia aren’t the only terms here. You need to use the Greimas rectangle and see that utopia has an opposite, dystopia, and also a contrary, the anti-utopia. For every concept there is both a not-concept and an anti-concept. So utopia is the idea that the political order could be run better. Dystopia is the not, being the idea that the political order could get worse. Anti-utopias are the anti, saying that the idea of utopia itself is wrong and bad, and that any attempt to try to make things better is sure to wind up making things worse, creating an intended or unintended totalitarian state, or some other such political disaster. 1984 and Brave New World are frequently cited examples of these positions. In 1984 the government is actively trying to make citizens miserable; in Brave New World, the government was first trying to make its citizens happy, but this backfired. As Jameson points out, it is important to oppose political attacks on the idea of utopia, as these are usually reactionary statements on the behalf of the currently powerful, those who enjoy a poorly-hidden utopia-for-the-few alongside a dystopia-for-the-many. This observation provides the fourth term of the Greimas rectangle, often mysterious, but in this case perfectly clear: one must be anti-anti-utopian.”

Kim Stanley Robinson

“Dystopia is good for drama because you’re starting with a conflict: your villain is the world. Writers on “Star Trek: The Next Generation” found it very difficult to work within the confines of a world where everything was going right. They objected to it. But I think that audiences loved it. They liked to see people who got along, and who lived in a world that was a blueprint for what we might achieve, rather than a warning of what might happen to us.”

Seth MacFarlane

“If we can make it through the second half of this century, there’s a very good chance that what we’ll end up with is a really wonderful world”

Jamais Cascio

“An adequate life provided for all living beings is something the planet can still do; it has sufficient resources, and the sun provides enough energy. There is a sufficiency, in other words; adequacy for all is not physically impossible. It won’t be easy to arrange, obviously, because it would be a total civilizational project, involving technologies, systems, and power dynamics; but it is possible. This description of the situation may not remain true for too many more years, but while it does, since we can create a sustainable civilization, we should. If dystopia helps to scare us into working harder on that project, which maybe it does, then fine: dystopia. But always in service to the main project, which is utopia.”

Kim Stanley Robinson

Saul Griffith’s S-Curves of Survival

Saul Griffith is always worth paying attention to – and his recent work at Rewiring America is no exception.

The way he breaks down the climate challenge into daunting-but-doable tasks is inspiring.

Making water heaters and kitchen appliances as appealing as Teslas is going to be hard-but-rewarding work for designers and engineers over the next decade.

As he says on his site:

I think our failure on fixing climate change is just a rhetorical failure of imagination.

We haven’t been able to convince ourselves that it’s going to be great.

It’s going to be great.

Saulgriffith.com

The sketched graph above is taken from Saul’s recent keynote for the Verge Electrify conference, which is on youtube, takes 12mins to watch, and is well worth it.

RIP Edward De Bono

Don’t know where my copy of ‘Children Solve Problems‘ is – probably on the bookshelf in my office that I’ve been back to once since March 2020.

It hasn’t had a lot of mentions in the obituaries I’ve read so far.

Not really a surprise, as he was so prolific, but it stands out for me.

As does the title sequence of the shows that he did on the BBC in the early 80s that I dimly remember watching with my dad (who I think had a copy of ‘Lateral Thinking‘)

From Ravensbourne’s excellent archive of BBC motion graphics:

A series of ten programmes about improving your thinking skills. Dr Edward de Bono showed that thinking, rather like cooking, was a skill which could be improved by attention and practice. The idea was to symbolically represent the scrambled brain, which then unscrambled and revealed the name of the programme. The artwork was done by hand without the aid of a computer, as this was created in the pre-digital era. The artwork was produced as black on white drawings pegged together in register. These were then copied photographically and printed in negative on Kodalith films and shot on a 35mm rostrum camera with red cinemoid gel behind the liths to add colour. The artwork had to be exceptionally precise, as if computer generated, in order not to shimmer and wobble. The glow was achieved by using a filter in the lens of the camera.

Animation artwork by Freddie Shackel.

Concept, design, art direction – Liz Friedman.

https://www.ravensbourne.ac.uk/bbc-motion-graphics-archive/de-bonos-thinking-course-1982

Thinking is like cooking.

Attention and practice.

Need to remember that.

RIP Edward.

RIP Dr Jonathan Miller

Station Identification

“Social media does not “get” not-fully-baked. Social media is useless for thinking out loud and exploring notions. Social media — bizarrely, given its nature — does not do context. I start a new notebook every year. Notebooks have internal context. Notebooks exist only to think about things, remember things and preserve things for later consideration. This is a notebook.”

Twenty years of Taklamakan

Bruce Sterling’s short story was published in 1999.

I figure he must have written it at least twenty years ago now.

I still think of it multiple times every year.

Severe annual resonance increases.

NAFTA, Sphere, and Europe: the trilateral superpowers jostled about with the uneasy regularity of sunspots, periodically brewing storms in the proxy regimes of the South. During his fifty-plus years, Pete had seen the Asian Cooperation Sphere change its public image repeatedly, in a weird political rhythm. Exotic vacation spot on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Baffling alien threat on Mondays and Wednesdays. Major trading partner each day and every day, including weekends and holidays.

At the current political moment, the Asian Cooperation Sphere was deep into its Inscrutable Menace mode, logging lots of grim media coverage as NAFTA’s chief economic adversary.

As far as Pete could figure it, this basically meant that a big crowd of goofy North American economists were trying to act really macho.

Their major complaint was that the Sphere was selling NAFTA too many neat, cheap, well-made consumer goods. That was an extremely silly thing to get killed about. But people perished horribly for much stranger reasons than that.

At sunset, Pete and Katrinko discovered the giant warning signs. They were titanic vertical plinths, all epoxy and clinker, much harder than granite. They were four stories tall, carefully rooted in bedrock, and painstakingly chiseled with menacing horned symbols and elaborate textual warnings in at least fifty different languages.

English was language number three.

“Radiation waste,” Pete concluded, deftly reading the text through his spex, from two kilometers away.

“This is a radiation waste dump. Plus, a nuclear test site. Old Red Chinese hydrogen bombs, way out in the Taklamakan desert.” He paused thoughtfully. “You gotta hand it to ’em. They sure picked the right spot for the job.”

“No way!” Katrinko protested. “Giant stone warning signs, telling people not to trespass in this area? That’s got to be a con-job.”

“Well, it would sure account for them using robots, and then destroying

all the roads.”“No, man. It’s like—you wanna hide something big nowadays. You don’t put a safe inside the wall any more, because hey, everybody’s got magnetometers and sonic imaging and heat detection. So you hide your best stuff in the garbage.”

Station Identification: Rule 110

“For the ‘One Hundred Billion Sparks’ album project I want to tell a story of our one hundred billion sparking neurones, and the magic which they create: our minds. Early in the story I aimed for the “nuts and bolts” of the processes involved, but not in the sense of showing a neuroscience lecture, I want to find the artistry and beauty of the natural processes involved.

Those are what make the richest visuals for my videos and live shows. Following this reasoning, one idea which came along, was to visualise a “Turing-complete” machine, which is a computer that is capable of performing any computation. This means the design of the computer is versatile enough to allow for any logical operation, within the constraints of the sorts of logical operations our usual computers can do. David Deutsch, amongst others, makes a convincing argument that human brains must also be universal computers in this sense, in his interesting new book ‘The Beginning of Infinity’. So I have some rough grounds at least, for making this link between brains and computers for the purpose of trying to get some hint of the visual essence of thought.

The interesting aesthetic link comes in via the work of Stephen Wolfram, from his 2002 book, ‘A New Kind of Science’, where he shows that simple “cellular automata” models, growing blocks of binary colour following simple rules, can create rich behaviours in their growth patterns, and even yield a system capable of Turing-completeness. Following a systematic exploration of the simplest possible rules governing cell duplication, Rule 110 is the first rule which displays Turing-completeness and is the simplest visual system that I know of which embodies this attribute.

The really interesting thing is that Rule 110 also displays a very particular visual aesthetic, that of a combination of order and chaos, never totally predictable or totally random. For me, that potential artistic/aesthetic link to universal thought is pretty amazing, and it’s also an aesthetic/property which appears in many other important places in nature (for example https://maxcooper.net/the-nature-of-nature), as well as being one of the main principles of my approach to music, where a healthy dose of disorder is always important.

After settling on this visual form for the project, I needed to create a piece of music which suited the retro blocky nature, which is something akin to Tetris. My immediate thought was big gated reverb snares and powerful classic synths. It had to be bold and clean in one the large scale, but also full of generative unpredictability.

It all fit nicely with what I like to do anyway, and just pushed me in a slightly more poppy direction than anything else on the album. The initial focused time was spent finding the killer chord sequence and bold patch, then setting up a generative seething chaos of synthesis with plenty of random waveforms and modulations, then a long time on the arrangement detailing with more than 100 layers of sounds. I finally added a vocal from Wilderthorn, which I chopped into destruction, just there to add a little hint of humanity in amongst the computation.

The final step in the process was to chat to the great visual artist, Raven Kwok, about the ideas and what I would like from the video. I was really happy when Raven showed me that he wasn’t just going to make an artistic interpretation of Rule 110, but had actually built his own version of the real system!

So the video shows an authentic pattern-generation of Rule 110, where we can see moments of repetition and pattern, but never in perpetuity, it always returns to disorder. The colours and 3-dimensional explorations are Raven’s extension of the basic system.

I still find it counter-intuitive that a simple deterministic system like this can yield undecidability in the content of its output, and I find it inspiring that this property relates to universal computation. It seems to me, at least, like the finest artistry.”